Steve Case and “The Third Wave” of the Internet

By Kevin Donley, multimediaman.org

In 1980, Alvin Toffler published The Third Wave, a sequel to his 1970 best-seller Future Shock and an elaboration of his ideas about the information age and its stressful impact on society. In contrast to his first book, Toffler sought in The Third Wave to convince readers not to dread the future but instead to embrace the potential at the heart of the information revolution.

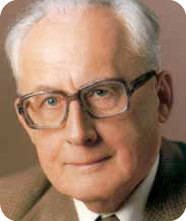

Alvin Toffler

Actually, Alvin—and his co-author wife Heidi Toffler—were among the few writers to appreciate early on the transformative power of electronic communications. Long before the word “Internet” was used by anyone but a few engineers working for the US Department of Defense—and after reporting for Fortune magazine on foundational Third Wave companies like IBM, AT&T and Xerox—Toffler began to hypothesize about “information overload” and the disruptive force of networked data and communications upon manufacturing, business, government and the family.

For example, one can read in the The Third Wave, “Humanity faces a quantum leap forward. It faces the deepest social upheaval and creative restructuring of all time. Without clearly recognizing it, we are engaged in building a remarkable new civilization from the ground up. This is the meaning of the Third Wave.” Appearing today as a little excessive, these words would certainly have seemed in 1980 to be a wild exaggeration by two fanatical tech futurists.

But Alvin and Heidi were really onto something. More than 35 years later, who can deny the truth behind Toffler’s basic ideas about the global information revolution and its consequences? The Internet, networked PCs, the World Wide Web, wireless broadband, smartphones, social media and, ultimately, the Internet of Things have changed and are changing every aspect of society.

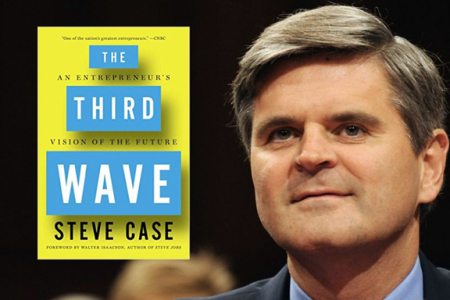

To his credit, Steve Case—who cofounded the early Internet company America Online—has written a new book called The Third Wave: An Entrepreneur’s Vision of the Future that borrows its title from Toffler’s pioneering work. As Case explains in the preface, he was motivated by Toffler’s theories as a college student because they “completely transformed the way I thought about the world—and what I imagined for the future.”

Steve Case’s The Third Wave

First Wave Internet companies

In Steve Case’s book, “The Third Wave” refers to three phases of Internet development as opposed to Toffler’s stages of civilization. For Case, the first wave was the construction of the “on ramps”—including AOL and others like Sprint, Apple and Microsoft—to the information superhighway. The second wave was about building on top of first wave infrastructure by companies like Google, Amazon, eBay, Facebook, Twitter and others that have developed “software as a service” (SAS).

Case’s Third Wave of the Internet is the promise of connecting everything to everything else, i.e. the rebuilding of entire sectors of the economy with “smart” technologies. While the ideas surrounding what he calls the Internet of Everything are not new—Case does not claim to have originated the concept—the new book does discuss important barriers to the realization of the Third Wave of Internet connectivity and how to overcome them.

Second Wave Internet companies

Case argues that Third Wave companies will require a new set of principles in order to be successful, that following the playbook of Second Wave companies will not do. He writes, “The playbook they need, instead, is one that worked during the First Wave, when the Internet was still young and skepticism was still high; when the barriers to entry were enormous, and when partnerships were a necessity to reaching your customers; when the regulatory system was coming to grips with a new reality and struggling to figure out the appropriate path forward.”

In much of the book, Case reviews his ideas about the transformation of the health care, education and food industries by applying the culture of innovation and ambition for change that is commonly found in Silicon Valley. However, he cautions that current Second Wave models of venture capital investment, views about the role of government and aversion to collaboration among entrepreneurs threaten to stall or kill Third Wave change before it can get started.

The story of AOL

In some ways, the most interesting aspects of Case’s book deal with the origin, growth and decline of America Online (AOL). Case gives a candid explication of the trials and tribulations of his innovative dial-up Internet company from 1983 to 2003. Case explains that prior to the achievement of significant consumer (27.6 million users by 2002) and Wall Street ($222 billion market cap by 1999) success, AOL and its precursors went through a series of near death experiences.

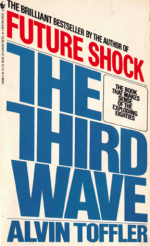

Steve Case in 1987 before the founding of America Online

For example, he tells the story of a deal that he signed with Apple in 1987 that was cancelled by the Cupertino-based company during implementation. Case had sold Apple customer service executives on a partnership with his then Quantum Computer Services to build an online support system called Apple Link Personal Edition that would be offered to customers as a software add-on. Disagreements between Apple and Quantum over how to sell the product to computer users ultimately killed the project.

Facing the termination of the investment funding that was tied to the $5 million agreement, Case and the other founders decided to sue Apple for breach of contract. Acknowledging their liability to Quantum, Apple agreed to pay $3 million to “tear up the contract.” Starting over with their new source of cash, Case and his partners restarted their company as America Online and they made an approach directly to consumers to sign up for their service.

This tale and others reinforces one of the key themes of Case’s book: Third Wave entrepreneurs will need to persevere through “the long slog” to success.

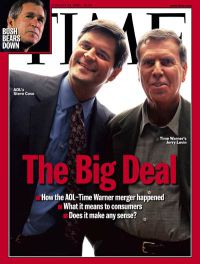

The January 24, 2000 cover of Time magazine with Steve Case and Jerry Levin announcing the AOL-Time Warner merger.

The end of Steve Case’s relationship with AOL is also a lesson in the leadership skills required for Third Wave success. In a chapter entitled “Matter of Trust” (the longest of the book), Steve Case relives the story of the merger/acquisition of Time Warner with/by AOL. It is a cautionary tale of both the excesses of Wall Street valuations during the dot com boom and the crisis of traditional media companies in the face of Third Wave innovation.

Case says that while the combination of AOL with Time Warner in 2000—the largest corporate merger in history up to that point—made sense at the time, two months later the dot com bubble burst and the company lost eighty percent of its value within a year. This was followed by a series of leadership battles that proved there were deep seated feelings of “personal mistrust and lingering resentments” among top Time Warner executives over the business potential of the Internet and the up-start start-up called AOL.

Steve Case writes that, although the dot com crash was certainly a factor, “It came down to emotions and egos and, ultimately, the culture itself. That something with the potential to be the first trillion-dollar company could end up losing $200 billion in value should tell you just how important the people factor is. It doesn’t really matter what the plan is if you can’t get your people aligned around achieving the same objectives.”

What now?

For those of us that were in the traditional media business—i.e. print, television and radio—the word “disruption” hardly describes the impact of the Internet over the past three decades. When companies like AOL were getting started with their modems and dial-up connections, most of us were looking pretty good. We had little time or interest in the tacky little AOL “You’ve Got Mail” audio message. As we reluctantly embraced IBM, Apple and Microsoft as partners in our front office and production operations, we were later making smug remarks about the absurdity of eBay and Amazon as legitimate business ideas.

IoT is at the center of Case’s Third Wave of innovation.

Steve Case’s book represents a timely warning to the enterprises and business leaders of today who similarly dismiss the notions of IoT. He points to Uber and Airbnb and shows that the hospitality and transportation industries are being right now turned on their sides by this new wave of information-enabled “sharing” businesses.

Actually, Case is an unlikely spokesman for the next wave of innovation having personally made out quite well (his net worth stands at $1.37 billion) despite the shipwreck that became AOL Time Warner. If he had been born twenty-five years later, Case could possibly have been another Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook and rode the Second Wave of the Internet (Zuckerberg got his start in coding by hacking AOL Instant Messenger) over the ruins of the dot com bust.

But that was then and this is now. Case has decided to commit himself to investment in present day entrepreneurships through his Revolution Growth venture capital fund. His book is kind of a roadmap for those who want to learn from his experience and bravely launch into the Third Wave of the Internet and build start-ups of a new kind. As Alvin Toffler wrote in Future Shock, “If we do not learn from history, we shall be compelled to relive it. True. But if we do not change the future, we shall be compelled to endure it. And that could be worse.”

During the twentieth century, printing technology made a major transition from mechanical to photomechanical and analog electronic to digital systems. The process took decades and by the 1990s all the technology of graphic arts production was impacted: design, text and image acquisition, typesetting, prepress, printing, binding and finishing. The result of this innovation was a dramatic improvement in the speed, quality, variety and complexity of printed material.

During the twentieth century, printing technology made a major transition from mechanical to photomechanical and analog electronic to digital systems. The process took decades and by the 1990s all the technology of graphic arts production was impacted: design, text and image acquisition, typesetting, prepress, printing, binding and finishing. The result of this innovation was a dramatic improvement in the speed, quality, variety and complexity of printed material.